‘Eid ul-Adha, the festival of sacrifice which coincides with the Hajj, is an important and hugely symbolic event. For the Hujjaj, who’ve just come from ‘Arafah, Muzdalifah and Mina, there’s release from the ihram and that moment when the knife slides across the throat of the sacrificial animal.

The ihram is not only the two white sheets worn by the male, or the modest covering of the woman; the ihram represents purity, a sublime innocence that has been the pilgrim’s condition on ‘Arafah.

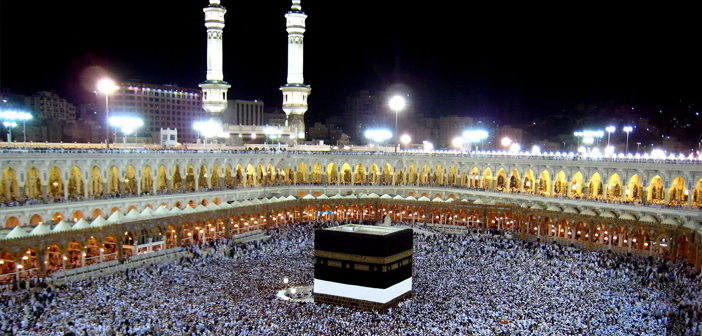

On ‘Arafah, where it’s haram for the believer to doubt Allah’s Mercy, the air would have been thick – not only with the dust of two million people – but the divine plasma of the Angels and Angelic Beings descending to earth.

Those who’ve been on ‘Arafah will know what I mean: the buzz of du’ah, the silence that falls just after Dhuhr and the energy of movement just before Maghrib, followed by a massive traffic jam and the stink of burning clutches.

In spite of technology, meaning and symbolism are found in every step of the Hajj. It’s one of the oldest devotional acts on earth, first consummated by Adam (as), refined by Ibrahim (as) and perfected by Muhammad (saw). Its ultimate reward is the Rahmah, the Mercy of Allah.

The Prophet Adam’s contribution to the Hajj is seen in his reuniting with Hawwa near Mina (the original word “muna” means “wish”) in answer to a prayer that Allah allows him to see his partner again after being cast out from Paradise.

Jabl Rahmah, the Mount of Mercy, is where Adam (as), the first prophet, stood begging for Allah’s forgiveness through the mercy of Muhammad (saw), the last prophet, whose name he’d seen embellished on the Holy Throne.

Forgiveness, which descends upon ‘Arafah, is due to Adam (as) who prayed that we be forgiven too. This is the state of the Prophets, what they desire for themselves is what they desire for their followers.

Nabi Ibrahim’s contribution centuries later is also hallmarked by tribulation and fortitude. Desiring a son, his first wife – Sarah – is barren. Concerned about his state, Sarah is inspired to allow him conjugal rights with Hajr, an Egyptian maidservant.

Sarah’s generosity to Ibrahim is a tribute to her outstanding character. Hajr is a younger, obviously more attractive woman, and yet – in spite of her emotions – Sarah has the strength to step back. For without Sarah’s contribution, the line of the Bani Hashim would not have produced Muhammad (saw).

In fact, the story of the Hajj is about Hajr and Sarah, the two Abrahamic matriarchs. Hajr gives birth to Isma’il – whose name is derived from sami’a, to “hear”. No sooner has she started suckling him, then she has to pack up and leave Bir Saba’at (modern day Beersheba) with Ibrahim (as).

Biblical sources cite Sarah’s jealousy for the reason why Ibrahim (as) was forced to travel 30 camel days into the desert and the valley of Bakka, which is modern-day Makkah. A more cautious understanding is that Ibrahim (as) was divinely inspired to do this.

One can only imagine the difficulty and the hardship of this journey. No-one consciously chooses to leave the comforts of home to traverse the desert with a new-born baby, and with no apparent destination.

Yet Hajr agrees to this. The point is that she didn’t have to. Even if the Biblical exegesis is accurate, she could so easily have chosen to stay in Hebron, which in those days, would have been far away enough from the house of Sarah.

And when their meandering journey comes to a halt, Hajr discovers Ibrahim (as) has to leave her on her own! Not only this, all the supplies he can leave her is a goatskin of water and a few dates. On the face of things, this is beyond comprehension, if not utter madness.

Because Ibrahim (as) was a prophet – and because Isma’il would become a prophet – there was a deeper significance; but at the time it would have been difficult to fathom, even with deep-rooted faith. In the moment, it must still have been an overwhelming experience for Hajr and Ibrahim (as).

After the joy of being granted a son, Ibrahim (as) now had to abandon him. The instant of Ibrahim’s departure from Makkah is one of the most touching in human history. This is because Hajr was not the doe-eyed stereotype of the submissive wife. Her question to Ibrahim (as) is astounding: “O, my husband, is it the will of Allah?”

When a distraught Ibrahim (as) had softly replied “yes”, she had let him to ride away over the black-ridged mountains with a heavy heart.

Of course, this did not ease the instincts of motherhood or the stress of what had happened. Hajr’s frantic scurrying between Safa and Marwa that led to the discovery of the Zam-Zam well must have been a terrifying ordeal. For if Allah had not granted Hajr the miracle of Zam-Zam, mother and son would have perished in days.

The Sai’, which is the ceremonial seven passes between Safa and Marwa in the ‘umrah, is a symbolic mercy beyond mercy. The drink of Zam-Zam when one has completed the Sai’, merely compounds these blessings. This is because the du’ah of Zam-Zam is what you intend it for.

But when all is said and done, no amount of chauvinism can deny this truth: that the blessings of the Hajj and the ‘umrah can be attributed as generously to women as they can be to men.

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us

1 comment

and one of them of african descent!! blessed africa mother of the most blessed prophet sawa