In a world in which members of all ethic, cultural and religious groups have fought for acknowledgement and respect, today we witness unparalleled intolerance directed toward specific groups. Within the Western Cape, however, community members have managed to continue to practice tolerance despite rising Islamophobia globally. This undeniable tolerance and acceptance, many may argue, is as a result of years of residing in close proximity, sharing in the struggles of the past, and sharing in each other’s celebrations.

An all-important aspect of Cape Town culture is the Easter Weekend, which is the commemoration of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, known to Muslims as Nabi Eesa (may peace be upon Him). The festivities take place over a long weekend and begins on Easter Friday with the preparation of a scrumptious dish of pickled fish. This celebration reflects the interfaith relations which exist within the Cape Town community.

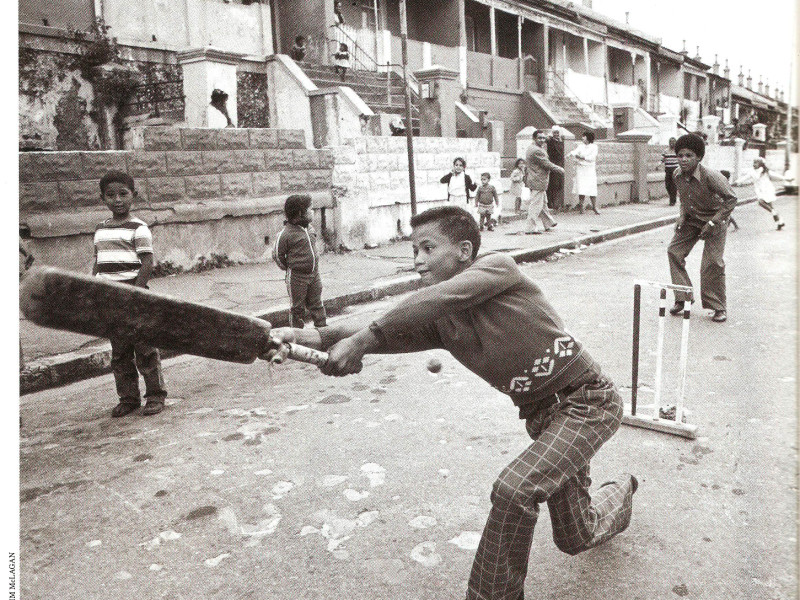

Life in the iconic District Six

No conversation about the culture of Cape Town can be entered into without mention of District Six. A culturally vibrant area, the history of District Six acts as a beacon of interfaith relations within Cape Town.

An ex-resident of District Six, Louisa Basson, and her entire family, inclusive of Muslims and Christians resided in the area in the 1950’s until the Group Areas Act was adopted.

Basson attended a church school, which was attended by both Christians and Muslims. She fondly remembers the fact that her Muslim friends embraced her and her religion at school.

“The focus was never on the religion, it was always on the fact that we are just children at school,” Basson noted.

The lines of faith were only noticeable when Muslim children prepared for “Moslem school”, an aspect of the Muslim culture that she asserts was “clearly understood and respected by all members of the community.”

“I remember I had a tiff with a Muslim friend and we decided to ‘fight it out’. I told her to put her Qur’an down so that we can fight, to which she replied that she cannot place her Qur’an on the ground. I then indicated that I will wait until she returns from ‘moslem school’ and does not have her Qur’an on her.”

This humorous story indicates the level of respect and understanding that each individual afforded people of different faiths.

Basson explained that when the “bilal bang” or the call to prayer for sunset prayers was made, children of all faiths were instructed to return home and refrain from making noise.

When the time of prayer for Muslim children dawned, parents and children of other faiths respected the sacredness of prayers. This form of education certainly added to the overall tolerance that individuals afforded to society in general.

Basson further noted that in her experience as a teacher, Muslim children previously respected the month of Ramadan (Fasting). Today, however, she finds that Muslim children wilfully disobey the laws pertaining to the month of Ramadan, despite her encouraging them to be dutiful toward their faith.

“In Muslim families and in Christian families I find that parents are not teaching children to respect their own religion. If the parents don’t teach respect, who is going to teach it?”

Basson’s experience emphasizes the role of community members of all faiths in raising children.

Excitedly, Basson recalls that the most important aspect of each year whilst growing up was the 10th of Muharram, a day of celebration in the Islamic faith. The 10th of Muharram in District Six was a day on which families handed out sweets and cakes to children in the surroundings. She fondly remembers all the numerous families that opened their homes on their day of celebration.

“I would like to say thank you to the Abbass family, who gave queues of children a ‘barakat’ (cake plate) irrespective of their religion – I don’t even know if they had financial problems, they shared so selflessly.”

She also noted that in the month of Ramadan all families dispersed plates of cake to neighbours of all faiths – “it was never an effort to share with everyone.”

The practice of dispersing cake-plates is a tradition that appears to be quickly dying out.

The religion of Islam encourages individuals to care for one’s neighbours. Though a neighbour may appear without troubles and financially stable, it is encouraged to share food, specifically during the month of Ramadan, so as to be certain that each fasting individual has ‘something’ with which to break their fast.

Basson yearns for the days when communities were integrated and embraced each other.

Bonds within communities in “old times” extended to taking care of all children within the community. Basson recalls her experience with the passing of her mother as one in which she received overwhelming care and support from community members of all faiths.

“There wasn’t a day that aunty Gava would not ask ‘did you eat?’ and community always looked out for us – like the village raising the child.”

As a testament to the communal nature of the era, all children understood that they were not allowed to disrespect any adult since any adult within the community had the ‘unspoken’ right to initiate discipline.

Strand, not just beaches

Strand, a town that today is synonymous with fishing, flea markets, and beaches is built on a rich history of strong community bonds and interfaith tolerance. An ex-resident of the Strand, Ebrahim Rhoode (78), who worked at the Strand Moslem Primary School for 33 years, later in life decided to research slave documents, which resulted in him writing a dissertation on his research. In 2014, his research was published as a readable book, titled: the Strand Muslim Community 1822 to 1966: A Historical Overview, with contributions by the late Maulana Yusuf Karaan and Professor Doria Daniels.

Rhoode asserted that wherever Muslims resided within the Western Cape, they lived in harmony with individuals of all faiths.

“If you look at the area of District Six today, you can see so many masajid (mosques) among the churches,” Rhoode noted.

Communities within South Africa resided in harmony until the Group Areas Act came into force. This resulted in the compartmentalization of communities based on race.

As a consequence of the Group Areas Act, “Indians” were forced into the Rylands area, whilst “coloureds” moved to Bridgetown and Bonteheuwel. He further noted that within the area of Strand, in which he resided, three mosques existed in close proximity to a church.

“The relations between Muslims and Christians were too beautiful. So much so, that when it was the time of magrieb (Islamic evening prayer) the Christian children instructed the Muslim children to head home.”

Most men within the community in the initial years, Rhoode further notes, worked as fisherman. There were, therefore, very few professionals.

He recalls that in 1943, one of the fishing boats capsized after being driven onto the reef by a freak wave. In the process, four Muslim fishermen sadly lost their lives. The community of the Wesleyan Church, which was located on the main road of Strand, held a memorial for the Muslim fishermen.

Practices of this nature empathize the bond of humanity as surpassing the thin line that separates each faith and community.

He further noted that the Malay Mission School at which he taught, accepted black children in defiance of South African law, which prohibited interracial relations. The school, in principle, accepted black children as the school that blacks were permitted to attend, was located kilometres away.

Tolerance and respect

Community members were, therefore, tolerant of each other’s differences, and assisted each other in every way possible. Rhoode explained that within his own family, his mother reverted to Islam at a young age. Today, he only has one surviving maternal-aunt, aunty Francis, who is 94 years old. Though aunty Francis is of the Christian faith, Rhoode notes, he loves and respects her as he would love his Muslim family.

He further notes that his Christian family would make special arrangements for halal food when hosting family functions.

This form of love and willingness to go the extra mile in order to cement family bonds is a testament to the nature of the upbringing that the elderly within our community insisted upon.

Rhoode asserted that as South Africans, we have been afforded religious and cultural liberties and should, therefore, work toward preserving this freedom.

“To have it is one thing, but you need to preserve it.”

It is, therefore, pertinent that the youth should be encouraged to learn about the past and the communities from which their parents and ancestors hailed. This will act as a means to understand and appreciate the role that each religious, cultural, and ethnic group has played in building the fabric of Cape Town. More importantly, this form of education will develop bonds of association, trust and love.

Where today communities are unable to maintain ‘intrafaith’ relations, individuals are urged to continue to preserve the culture of our ancestors, who sought to nurture communities on the backdrop of social oppression.

“You can only be proud of your heritage if you know about your past.”

VOC (Thakira Desai)

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us

1 comment

Daar is baie gesels oor die feit dat Flori Schrikker as Christen en Koelsoem Kamalie as Moslem so nou met mekaar saamwerk. http://www.litnet.co.za/us-woordfees-2016-kosdemo-kook-saam-kaaps/