OPINION by Haroon Moghul

We need you, Muhammad Ali.

Now, more than we have in a very long time. But you left us. You moved on. Friday night, a few days before Ramadan, the world’s most famous Muslim — a world champion three times over, an Olympic gold medalist, a superstar, a folk hero, a global icon, the man who called himself the greatest in the world — went back to God. He had been ill for some days now. It was only, we feared, a matter of time. But the loss we saw coming hits deeply, awfully close to home.

[Muhammad Ali, boxing icon and global goodwill ambassador, dies at 74]Think of a Muslim these days and, let’s be honest, you might sarcastically (or, worse, seriously) come up with President Obama. Your mind might throw up Osama bin Laden. You might even struggle to come up with someone. In the American mind today, Islam is foreign, alien, dangerous, threatening, menacing. For many Americans, Islam is so contradictory to American values that a good chunk of us seem to think it should be banned.

Donald Trump wants to keep Muslims out of the country, and a majority of Americans — not just Republicans — agree with him. No matter how odious the remarks, the policies, the proposals, if they win votes, they have to be reckoned with. And you know what? They win votes. Hating Muslims wins votes.

There are not many American Muslims, which might be why we’re such a convenient punching bag. Probably 4 million or 5 million of us. A percentage point. A smaller share of the population than in many other Western nations, such as England, France or Germany. But what makes American Islam unique, different, rooted was Muhammad Ali.

Or, rather, what he represented.

Some one-third of American Muslims are African American. Some one-third of American Muslims have roots in this country that go back to, well — TV just remade the series “Roots,” and Kunta Kinte is explicitly Muslim. How did Americans convince themselves to vote for a lanky black guy named Barack Obama? A friend once suggested, in all seriousness, that we are used to black men with Arabic names, that these are not unusual or strange: Shaquille O’Neal, after all. Jamaal Wilkes.

A large percentage of the slaves brought here in chains were Muslims. Some historians believe that some of them held on to Islam against all odds for decades, and that the various Muslim religious forces unleashed in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s weren’t just a kind of Muslim Great Awakening, but a Reawakening. The Moorish Science Temple. The Nation of Islam. The women and men who established — or, you might argue revived — Islam in America, who give us names we should all be familiar with: The Honorable Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm X, the preacher who broke with that teacher and turned to Sunni Islam, and was soon assassinated.

Muhammad Ali was one of them. But he remained with the Nation, repudiated Malcolm and then, years later, converted to Sunni Islam, too, and regretted his rejection of his former friend, who was assassinated in 1965. Elijah Muhammad’s son Wallace Muhammad carried the community into mainstream Sunni Islam. Louis Farrakhan leads those who refused to go along. Even now, as this history is suppressed, forgotten, overlooked, denied, supplanted by the narrative of Islam as beyond the pale, utterly and irredeemably barbaric, it is still a fact that some of America’s most prominent Muslims are African Americans: The two Muslims in Congress, Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.) and Rep. André Carson (D-Ind.). Comedian Dave Chappelle. Artist Mos Def, now known as Yasiin Bey.

But there is something different about Muhammad Ali still.

[Ali’s athletic greatness was merely a platform for the larger man]Malcolm X died in February 1965, only 39. I used to wonder: What might he have done had he lived?

Several years ago, I sat down with a Danish journalist in the wake of controversy over Jyllands-Posten’s Muhammad cartoons, which have provoked such ire and tragedy. Most of the questions I was asked were predictable, but not the last one. “Do you think,” the journalist asked, “that if the prophet Muhammad were alive today, he would be a good American?” I must have mumbled some half-assed, ordinary answer, so pedestrian that I was not quoted; on the walk home, I realized that my response was deeply inadequate. No, the prophet Muhammad would not have been a good American. He was one of those rare human beings so great that he transcended his ethnicity, his context, his history, and became truly global. Like Jesus or Buddha; Martin Luther King Jr. or Nelson Mandela.

When Muhammad Ali traveled to the country then called Zaire to fight George Foreman, thousands of young men and women lined up to meet him, chanting, “Bumaye, Ali!” (“Kill him, Ali!”) Before social media, before satellite television, before the Internet, he was a genuinely global phenomenon, which makes his popularity even that much more remarkable, even as it might now be hard to comprehend.

Part of this is Americana, whose force we might forget. Because America is the most powerful country in the world, we are known, feared, admired, resented, copied. But African America has a force perhaps greater than any other part of America, because the historic legacy of oppression and injustice, in the context of the hyper-power that we are, means that the black struggle for freedom quickly becomes a global struggle, if not the global struggle. It’s why hip-hop has been not just adopted but embraced as the language of resistance and pride and steadfastness from inside the siege of Gaza to the suburbs of Paris.

But part of it was Muhammad Ali.

He did everything you are not supposed to. He fought and won a gold medal, and then said he cast it into the water, disgusted by the apartheid hypocrisy of the country he represented. He abandoned a name given to his family by slave masters and took on a new name. An Arabic, allegedly foreign one. He refused to fight in Vietnam, issuing an eloquent, unforgettable denunciation of imperialism, aggressiveness and war:

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?

No, I am not going ten thousand miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would put my prestige in jeopardy and could cause me to lose millions of dollars which should accrue to me as the champion…

I either have to obey the laws of the land or the laws of Allah. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail. We’ve been in jail for four hundred years.”

He refused to be taken in by blind, superficial patriotism. He stared down America, sacrificing his career, his freedom, his reputation. Where Donald Trump ran away from the draft with the cowardly privilege of a ridiculous medical excuse, Ali rejected the draft on moral grounds, and he paid the price. But America blinked first. He held firm, and held out, and did what was right, and better and more moral, a Muslim famous, mind you, because he refused war, and saw it as unconnected to freedom and liberation, who preferred to fight in the ring, who used his words as his weapons, whose cause was equality and dignity at home instead of mindless wars abroad, the mass slaughter of innocents in a country we had no business in anyhow.

And the reason I bring Trump up is not to point out how it must have felt to Ali, a proud, fearless black man, unbowed all those years, in the twilight of his life, to see the return of white nationalists into the public sphere, to see the ridiculousness of anti-Muslim bigotry resurrected when he might have hoped we’d left it behind, not even to tell you how it feels, as a Muslim American who desperately clung to the Xs and Alis and Jabbars as proof that I belonged here, that my religion was part of here, but to say that Donald Trump is all the proof you need that Muhammad Ali is the greatest in the world. Is, not was.

When President Obama spoke at the Islamic Society of Baltimore in February, he noted the many contributions Muslims made to America, including as “sports heroes.” Trump tweeted in mockery: “What sport is Obama talking about, and who? Is Obama profiling?”

Friday night, however, Trump — ever oblivious to the irony, the very man who winks at Klan members, who encourages extremists into the body politic, who inspires terrorists — tweeted a brief, typical eulogy of Muhammad Ali:

Muhammad Ali is dead at 74! A truly great champion and a wonderful guy. He will be missed by all!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 4, 2016

The most prominent racist and Islamophobe in America today, the presumptive Republican nominee, could not ignore him; even as he calls for Muslims to be banned from the country, he hailed Muhammad Ali.

On Fox News on Friday night, tributes to Muhammad Ali poured in, on a channel that usual derides Muslims as a matter of course.

That is how great Muhammad Ali is. I say is, not was: a great American, a great Muslim, a great African American, a great boxer. And above all, a great human being.

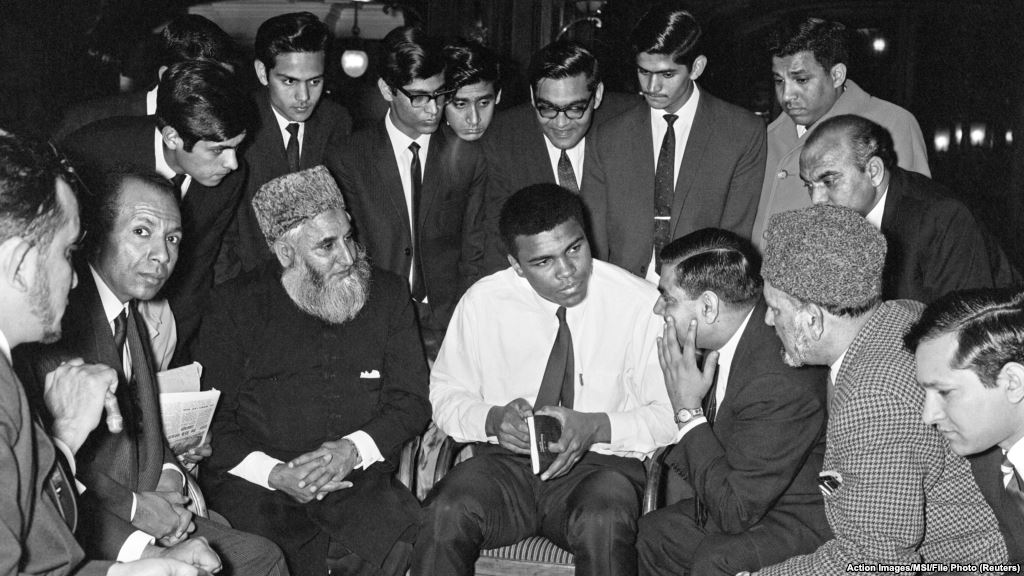

My father recounts listening to his bouts on tinny radios in Pakistan in the 1960s, and millions of Pakistanis will tell you they did the same. He was the world’s champion. Of the poor, the dispossessed, the marginalized, who used his fame, his tongue, his fists, to try to stop wars, to liberate peoples, to call us to something better.

Without people like Muhammad Ali, a man whose first name and last name would put him on a terrorist watch list, who we have divorced from the biases we still apply, who is too great, too powerful, too resonant, to be reduced to a stereotype, America today would not be unrecognizable: We know our history. America would just be undesirable.

He was also the greatest because, and I hope you’ll pardon the plagiarism, he made us great. He turned the democracy we boasted about into something we actually practiced.

In the Muslim tradition, when someone dies, we say, ‘To God we belong, and to God we are returning.’ Friday, the greatest returned to the greatest. Rest in peace, Muhammad Ali. Rise in power.

Haroon Moghul is a senior fellow and director of development at the Center for Global Policy. His next book, “How to be a Muslim,” will be published in 2017.

[Source: Washington Post]

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us