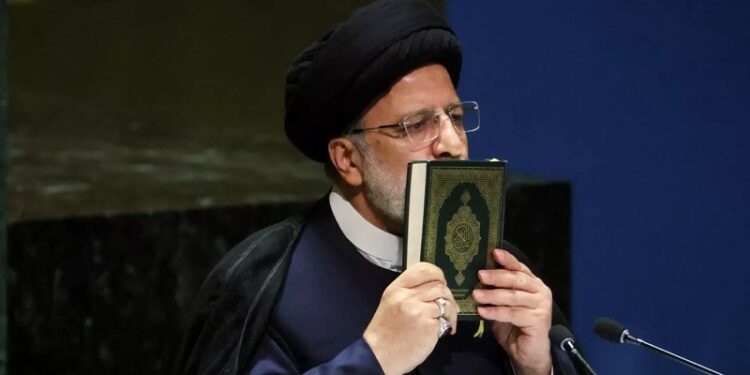

Ebrahim Raisi is Iran’s president. He’s a principilist cleric with fiercely conservative beliefs who headed the judiciary for four years. But is he an ayatollah?

Yes, according to his entourage, who have been referring to him as such ever since he assumed the presidency two years ago.

Not everyone agrees. And in the Islamic Republic of Iran, where religious rankings carry significant political weight, the debate carries a question of legitimacy for the president, particularly if he eyes the greatest prize of all: the position of supreme leader.

A group of reformist-leaning clerics, including senior figure Hossein Mousavi Tabrizi, insist Raisi can’t be considered an ayatollah – the second-highest rank of Shia clergy after grand ayatollah – based on his level of clerical knowledge.

According to Tabrizi, Raisi simply does not possess the necessary qualifications, as he has not reached the level where he can perform ijtihad, where ayatollahs make jurisprudential rulings based on their own understanding of Islamic principles. Scholars qualified to perform ijtihad are known as mujtahid.

A more indirect rejection of Raisi being referred to as an ayatollah has come from Mohammad Taqi Fazel Meybodi, a member of the assembly of researchers and teachers at the seminary at Qom, Iran’s holiest city.

In a veiled reference to the president, Meybodi said someone who left their studies at the seminary many years ago and engaged in governmental work without pursuing further religious education cannot be regarded as an ayatollah.

Drawing parallels with academia, he noted someone can only be recognised as a doctor after completing all the required processes, such as comprehensive exams.

Ayatollah becomes political

The politicization of the ayatollah title can be traced back to the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Following the revolution, clerics began occupying executive and governmental positions, which gradually transformed the clerical titles into political tools for elevating clerics’ status.

A prominent example of this is seen in the case of the current supreme leader, Ali Khamenei. Prior to assuming leadership in 1989, he was referred to as hujjat al-Islam, a mid-ranking clerical title. However, upon assuming office as supreme leader, he came to be addressed as an ayatollah, signifying a promotion in his clerical rank and political authority.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a cleric teaching at the Qom seminary told MEE that in the past no one without the requisite training would have dared claim to be a marja talqlid, or source of emulation, as ayatollahs are known.

“Today, unfortunately, the situation is reversed and sometimes they are quick to claim titles even though they know that there are people with more knowledge and expertise in ijtihad,” he said.

The cleric feels that tying religious titles to administrative and political clerics has undermined the theocratic hierarchy and the positions of the clergy themselves.

“Sometimes, a cleric who has not taught at a seminary or reached high levels of scholarship is bestowed the title of ayatollah simply because they assume a management or political position. This practice occurs even when they have not attained the level of ijtihad,” he said.

He believes grand ayatollahs should issue serious warnings to government officials regarding inappropriate claims of the ayatollah title and put an end to such practices.

The cleric, too, believes Raisi lacks the necessary knowledge to be able to perform ijtihad as an ayatollah.

Raisi isn’t the only official bestowed the title of ayatollah for political reasons. Principilists also insist on using the term for ultraconservative clerics Ahmad Khatami and Ahmad Alamolhoda, prayer leaders for Tehran and Mashhad respectively, increasing their prominence.

On the other side of the political divide, reformists have been known to do the same with Hassan Khomeini, the grandson of the founder of the Islamic Republic Rohollah Khomeini, who they want to succeed Khamenei as supreme leader upon his death.

“Aspiring to leadership positions necessitates the ayatollah title as the leader must be a mujtahid. Consequently, Raisi’s team is making concerted efforts to portray him as an ayatollah, aiming to pave his way for the leadership race,” he said.

“However, their endeavours have so far fallen short, as Raisi’s educational background and scholarly achievements do not parallel those of Khamenei and Hassan Khomeini. In fact, he has not pursued any significant studies.”

From scholar to judge and back again

Raisi’s career has been overwhelmingly pursued in the judiciary.

In the decades following the Islamic Revolution he’s been prosecutor general of Karaj, chairman of the General Inspection Organisation, Tehran prosecutor general and the deputy head of the judiciary.

In March 2016, his trajectory took a significant turn. With his career seemingly plateaued at prosecutor general, Khamenei gave Raisi a momentous boost by tasking him with chairing the custodianship of the holy shrine of Imam Reza, the revered eighth imam of Shia.

This prestigious position granted him oversight of wealthy companies under the shrine’s purview.

Notably, before he took up this position he was officially addressed as a hujjat al-Islam, a title two ranks below that of ayatollah. Once he assumed the custodianship in Mashhad, however, principilist media swiftly bestowed the title of ayatollah on him.

Even Raisi’s personal website began referring to him as an ayatollah. Simultaneously, Raisi began teaching advanced clerical studies.

“Teaching advanced clerical studies has turned into a new way for political clerics to prove they have reached the degree of ijtihad, while this is all nothing but a ploy,” the Qom-based cleric said.

A year later, with his standing in the clerical hierarchy enhanced, Raisi entered the race for the presidency with the unwavering support of principilists (sometimes known as hardliners), the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and influential conservative factions. It was a competition he would eventually win in 2021.

Clerical knowledge

A senior cleric based in Qom shed further light on Raisi’s religious education, telling MEE: “Raisi studied Arabic literature in Mashhad for one or two years, and then went to study at the seminary in Qom.”

At Qom, the senior cleric said, he took classes until the level where he studied Kitab al-Luma, or the Book of Light, a 10th century study of Sufism that is considered by Shia clerics to be an essential text to understand the basics of jurisprudence.

“In the first part of a student’s jurisprudence education, he needs to be taught Kitab al-Luma, which takes two or three years.”

Yet Raisi’s religious education appears to have gone no further following his Kitab al-Luma studies.

“Raisi lacks sufficient clerical knowledge since he did not complete the extensive years of study required for comprehensive understanding. In the traditional path, a student typically dedicates a minimum of seven to eight years to basic studies and then continues with advanced studies for approximately 15 years,” the senior cleric said.

“This rigorous educational process is necessary to develop the capacity to teach and derive legal rulings from the Islamic sources.”

The senior cleric added: “The title of ayatollah should not merely be granted based on external factors, such as a person’s long beard or financial status. True scholarly expertise and dedicated years of study are crucial factors for the attainment of such a prestigious title.”

Source: Middle East Eye

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us